Haaf fishing in Shetland

Shetlanders have always had a close relationship with the sea as a source of food, transport, trade and a way to escape the poverty of the croft. However, one period of history involving Shetlanders and the sea stands out. This was the Haaf fishing, which took place between 1750 and 1900.

To get home they navigated by the sun, stars, and da moder dy – an underlying sea swell that always moved towards the land.

Haaf fishing involved spending 2-3 days at sea in big, open, six-oared wooden boats, sailing up to forty miles out to the fishing grounds, using landmarks for navigation, setting 6 miles of lines, hauling them in again and then sailing the 40 miles back with a boat full of fish. If there was no wind, the 6 man crew rowed the huge distance!

Before Haaf Fishing

Shetlanders always fished the water around the islands – but most of this was subsistence fishing, done inshore with handlines and small boats, the catch being for their own consumption. When longlines were introduced after 1700, boats started to slowly venture further afield.

From the 15th to the 17th century, Shetlanders would trade salted cod, ling, herrings, butter, wool and much more with the Hanseatic League of German merchants, in exchange for hooks, lines and nets, biscuits, beer, fruit and money. However in 1707, the Act of Union introduced high duties on imported salt, which was crucial for curing whitefish, and meant that the German merchants could no longer afford to trade in Shetland.

The truck system

Local merchant-lairds seized upon this opportunity; acquiring ships and, by 1730, they were exporting fish, especially ling, to Europe. The merchant-lairds made a lot of money selling the fish, but the truck system meant that they weren’t really paying the men who were doing the fishing for them!

Crofters in Shetland were tied to these merchant-lairds who owned the crofts which housed their families. In the days before the crofting act there was no security of tenure. The merchant-lairds had already divided crofts into smaller units which were much less profitable for their tenants. The crofter therefore had to turn to fishing to feed and house their families. It was either that or their wives and children went homeless.

The merchant-lairds supplied boats and gear in exchange for the right to buy the men’s catch. With no wage being involved, the men were paid rock bottom prices for the fish they brought ashore, often in credit notes. While they were at the fishing stations the men were also charged for the things they bought, such as tobacco. Sometimes, at the end of a back-breaking summer of work, the men ended up going home owing money to the merchant. If they did make money it was perhaps just enough to pay their rent to that same merchant. This was the truck system, which became wide-spread in Shetland, and was almost a form of legalised slavery.

With the threat of losing their homes looming over their heads, the fishermen often took dangerous risks to catch as much fish as possible.

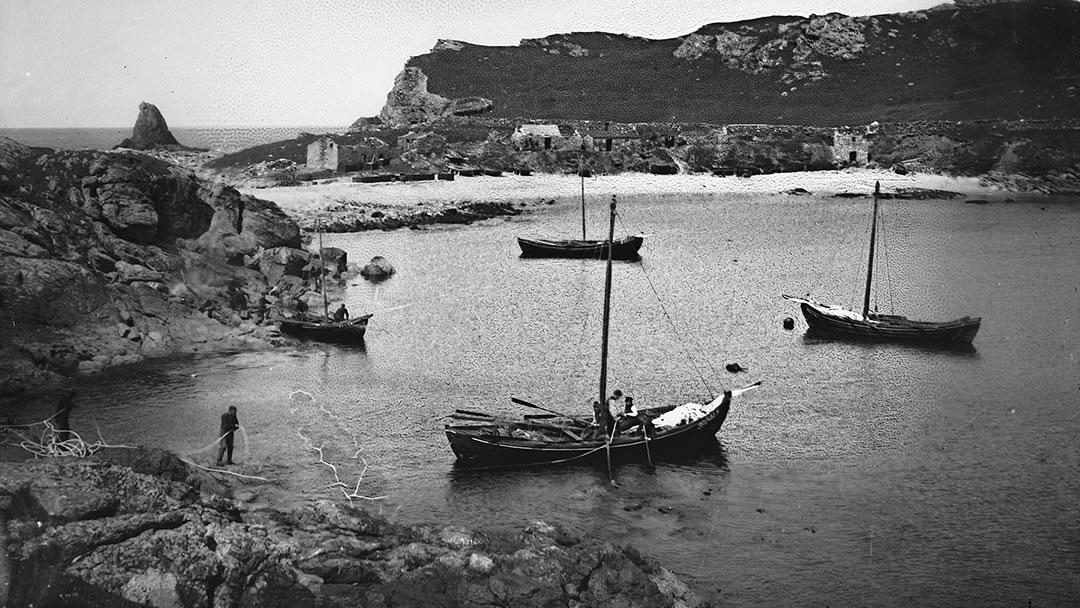

What were the haaf-fishing vessels like?

In Shetland every family had a boat for day to day work, and most of them had four oars. The six-oared Haaf fishing vessels were a bit bigger than these and grew as time went on, becoming harder to handle. However, the bigger the boat you had, the more fish you could catch at any given time without having to go back to shore to offload it.

In appearance the vessels looked like very large rowing boats. They were crewed by six men who manned a single oar; giving them the name ‘sixareen’. These boats also had a square sail which would be used if the wind was blowing in the right direction.

Sixareens were clinker-built; a technique used by Norsemen; where the edges of the hull planks overlap. Originally a lot of the sixareens came in kit form. They were built in Norway and then taken apart and assembled again in Shetland. Latterly Shetlanders learned the techniques for boat building themselves and built their own sixareens. Every scrap of wood however, had to be imported.

The boat was divided into six rooms or spaces:

- The fore head was where sails and tackle were stored.

- The fore room where provisions for the trip were stored.

- The mid room was where stones for ballast were placed.

- The owse room was kept clear for bailing out water.

- The shot room was the biggest room – where the fish was stowed.

- The kannie was the helm, where the skipper sat when the vessel was under sail. When she was being rowed the skipper manned an oar.

The compartments were separated by the tafts (seats), and under these were wooden ribs called fiskabrods, which prevented the fish from sliding out of the shot room into the rest of the boat.

There were between 300 and 500 sixareens in Shetland. The Haaf fishing proved to be a hard life for these boats and they only tended to last 5 or 6 years. When they finished their lives as a fishing vessel some ended up being used as a flit boat for moving livestock, peats and other goods between islands or from ship to shore. The sixareens may eventually have ended up as the roof of shed or outbuilding. Nothing was ever wasted in Shetland, especially if it was wooden!

What was life like on board?

The men would travel up between 20 and 40 miles offshore. As the men were dealing with a prevailing wind, they could usually only sail in one direction. They were always happier if they could row out with a relatively light boat and sail back with a heavy load of fish!

When they reached the fishing grounds, the fishermen would barely be in sight of the highest hills in Shetland. They would have sea all around them. They would set the lines; up to six miles of line from the boat, which were baited with haddock or young saithe caught by the older men at the station, and then they would wait for the tide to turn.

While they were waiting, the older men would tell stories to the younger ones. They had a metal kettle with a peat in it so that they could warm a cup of tea. The men usually took brönies with them to eat; these were oatmeal or beremeal cakes. It was simply a matter of waiting; there wasn’t much else they could do.

If they wanted to sleep, they would take it in turns and crawl under the sail. In an open boat, that was the only shelter they really had. If it came on rain they would spread the sail out on top of everybody and try to shelter underneath.

When the tide turned, the men would haul up the lines, a process which took four to five hours. The ballast stones would be cast overboard as the fish were stowed. If they got a good shot and could fill the boat, then they would head for home. If they didn’t get enough to fill the boat the men would set the lines again and wait for the turn of the tide. If they weren’t catching fish then the fishermen could be at sea for two or three days.

To get home they navigated by the sun, stars, and da moder dy – an underlying sea swell that always moved towards the land. Ronas Hill, the highest in Shetland, was also used as a landmark to guide fishermen back from the fishing grounds west of Shetland to the Haaf fishing stations. Saxa Vord served the same purpose for boats fishing to the east.

The men would make this trip two or three times a week.

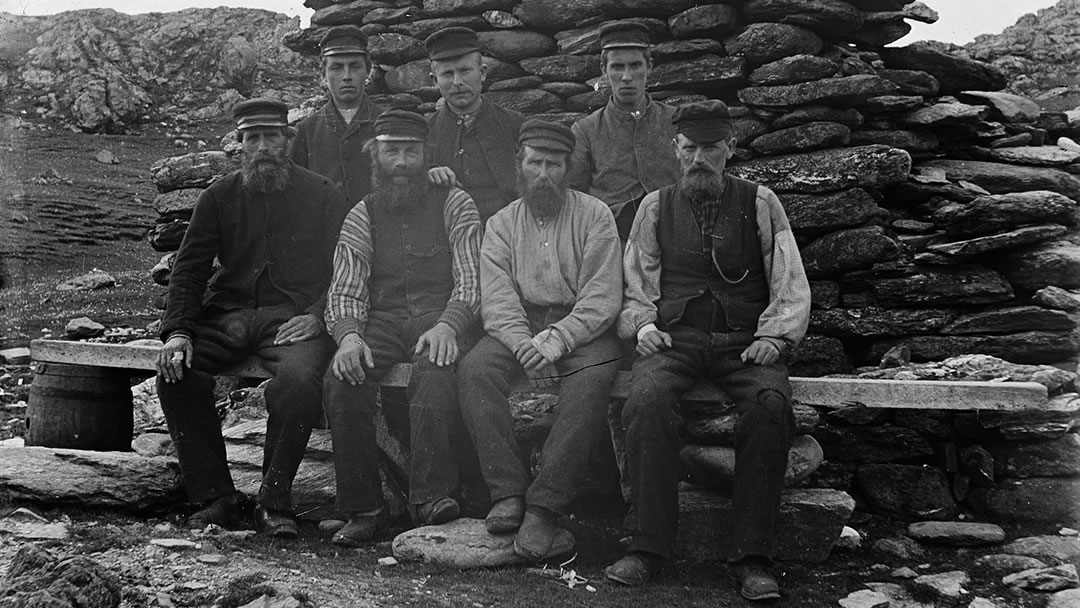

What was life like at a Haaf fishing station?

There were about a half a dozen large Haaf fishing stations in Shetland – the main ones being Fethaland, Stenness, Gloup and Hillswick. These were all to the north of Shetland, close to the fishing grounds. There were also many smaller places that the men fished from but then landed their catch on the drying beach of the big Haaf fishing stations.

There was also an extensive haaf fishery around Scalloway and Burra but this was closer inshore and the fishermen were able to return home when not fishing.

The Haaf fishing season was short, from early May to late August, but during this time the Haaf fishing stations were busy places. In those days there were 30,000 residents of Shetland compared to 20,000 today. There was a summer migration from the centre of Shetland to the coastline because of the Haaf fishing. In Fethaland alone there were around 800 men.

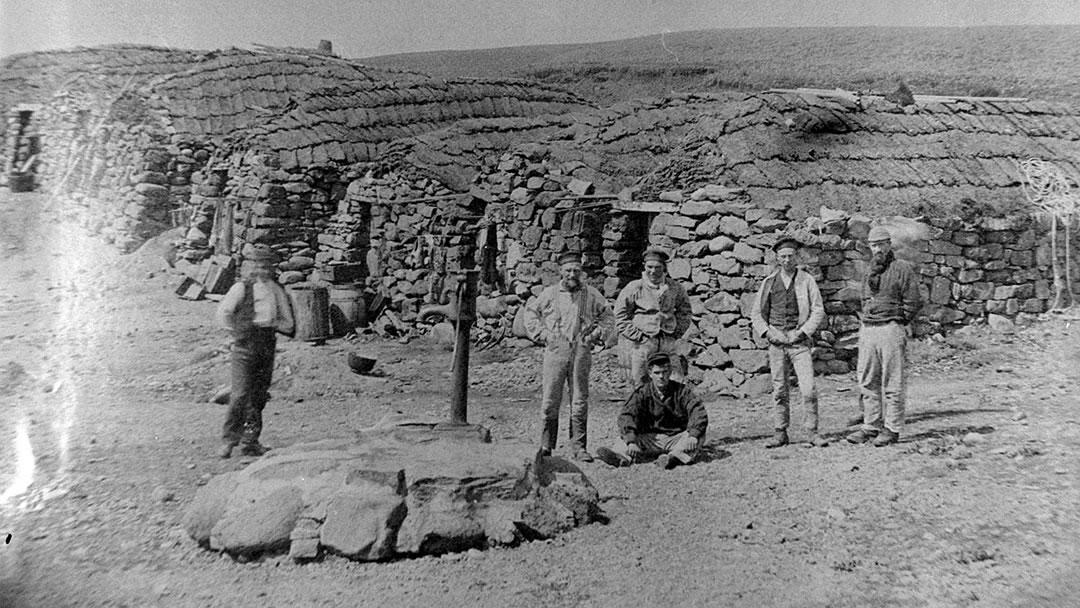

The fishermen lived in drystone lodges – the roofs of which had to be removed at the end of every season. The roofs were made of wood and turf and they would have been damaged by the winter storms! Lodges can still be seen at Fethaland, and there’s a cootch kettle at Hillswick. Cootch was used to treat the long lines and helped to prolong their life.

Each station also had a böd. This was a larger building which housed the laird’s factor, usually on an upper floor. The ground floor was used to store salt, tar, rope and the essentials of life to be sold to the fishermen.

Haaf fishing stations were based at pebble beaches. This is where the fish were split open, boned, washed, layered with salt and then left, the flesh side uppermost, to dry. The livers were melted down and the oil was barrelled. The fish would be stacked and as it dried it shrank and salt or ‘bloom’ would appear on the surface. Curing the fish took place as soon as the boats came in. The work was done by older men and beach boys; lads too young to go to sea. The fish, once dry, were stacked in the böds or in a fish-cellar to be collected by cargo ships bound for Spain at the end of the season.

The fishermen only had one break during the summer; a weekend off at Johnsmas (24th June). If a man lived locally to the station he may have nipped home at the weekend as the men tended come ashore for Sunday unless they were stuck out at sea for some reason. Other than that, they never went home.

At the end of the season the men would return to their crofts. During the winter they might fish inshore for haddock, 5 or 6 miles off, for themselves and to sell in Lerwick. They also had crofts to take care of and repairs to make to their houses.

Dangers and disasters

Haaf fishing was very dangerous due to the unpredictable nature of the weather far out at sea. However, when you look at the numbers of men that fished and the length of time that they fished for, the actual disasters are relatively few.

However, when disasters happened, they devastated the coastal communities. On 16 July 1832, a severe gale sank 17 boats and 105 men were lost. On 20th July 1881, hurricane force winds caught the fishermen by surprise. The boats that tried to come home were mostly capsized or swamped, but those that stayed at their lines for the most part survived. In all ten boats foundered and 58 Haaf fishermen lost their lives. They left behind 34 widows and 85 orphans. Six of these boats and 36 of the men were from the fishing station at Gloup in North Yell. It was a tragic loss for a small community.

Though it was dangerous, the fishermen had confidence in their boat and skipper and it was this belief; that he would bring them home, and the threat of getting thrown off their crofts, that kept men going out.

Why did Haaf fishing come to an end?

The two major fishing disasters in 1881 and 1900 signalled the beginning of the end for Haaf fishing. The herring fishery in the 1880s and the Crofter’s Act of 1886, which put an end to the truck system, were two more nails in its coffin.

Larger safer boats were introduced and undecked sixareens were replaced by fully decked smacks. Fishermen could finally install a few home comforts. However, when the steam trawler was introduced, longlining in large sailing boats couldn’t compete economically. Haaf fishing stopped quite quickly at this point.

There are few sixareens left in Shetland. There are a couple of replicas and bits and pieces lying around here and there. At the Shetland Museum and Archives there’s a replica sixareen called the Vaila Mae. She sails regularly in Lerwick Harbour and you can even get a trip on her during Shetland Boat Week!

One of the only surviving sixareens from the past can be seen in the Shetland Museum and Archives. She was built as the Foula mail boat, which fished for a little while and then ended up as a flit boat for shifting peats. She didn’t spend much of her life as a fishing sixareen.

It’s still quite something to see her up close though; to imagine the difficult life that men had, rowing such a distance and fishing so far away from home. It’s quite something to think that six fishermen lived on this boat for two to three days, with danger surrounding them and the threat of losing their homes hanging over their heads. It’s difficult, in such a lovely place as Shetland, to imagine a life so hard.

With grateful thanks to Davy Cooper from the Shetland Amenity Trust for his help in writing this article.

By Magnus Dixon

By Magnus DixonOrkney and Shetland enthusiast, family man, loves walks, likes animals, terrible at sports, dire taste in music, adores audiobooks and films, eats a little too much for his own good.

Pin it!